David Moser

True Colors

1 / 0

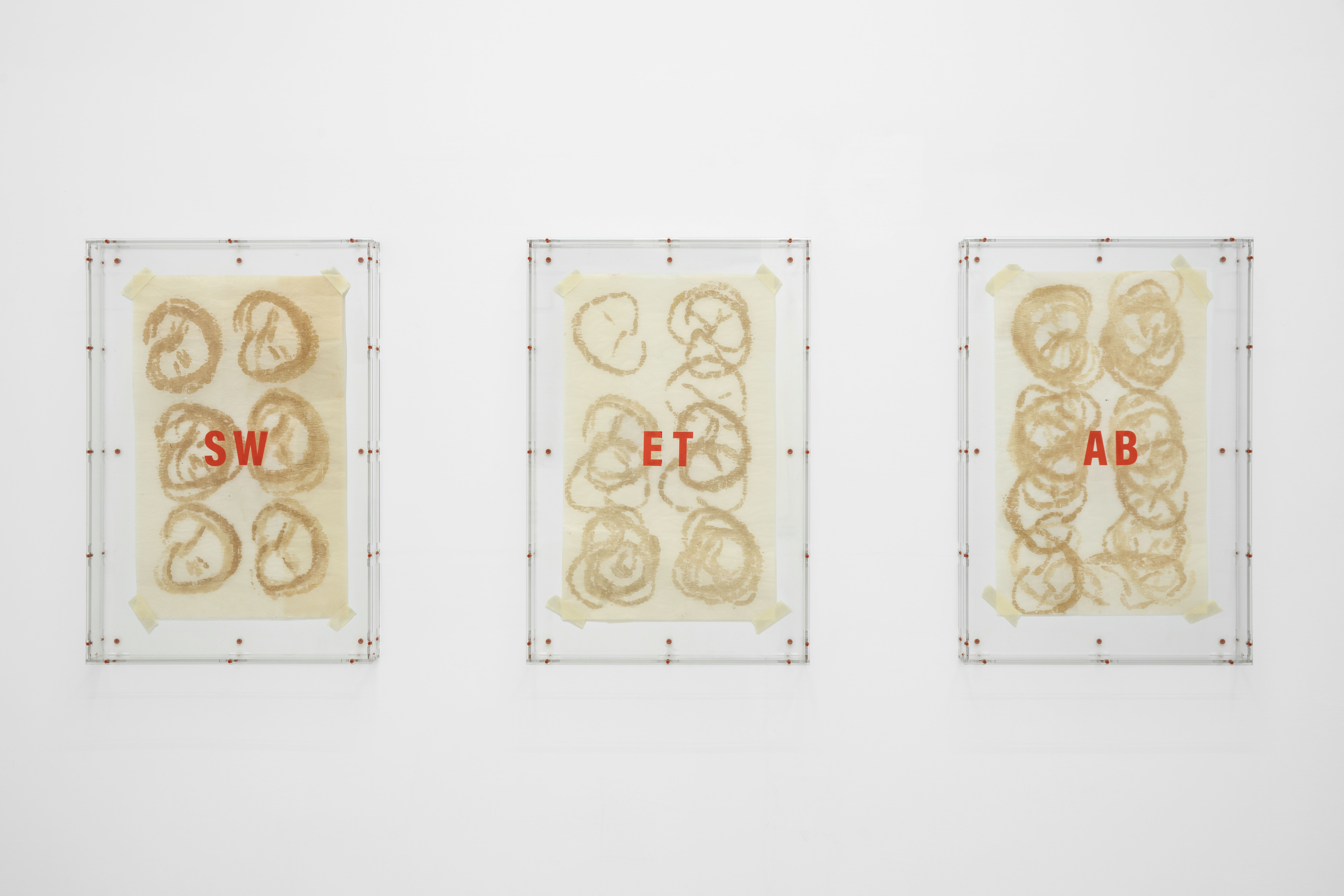

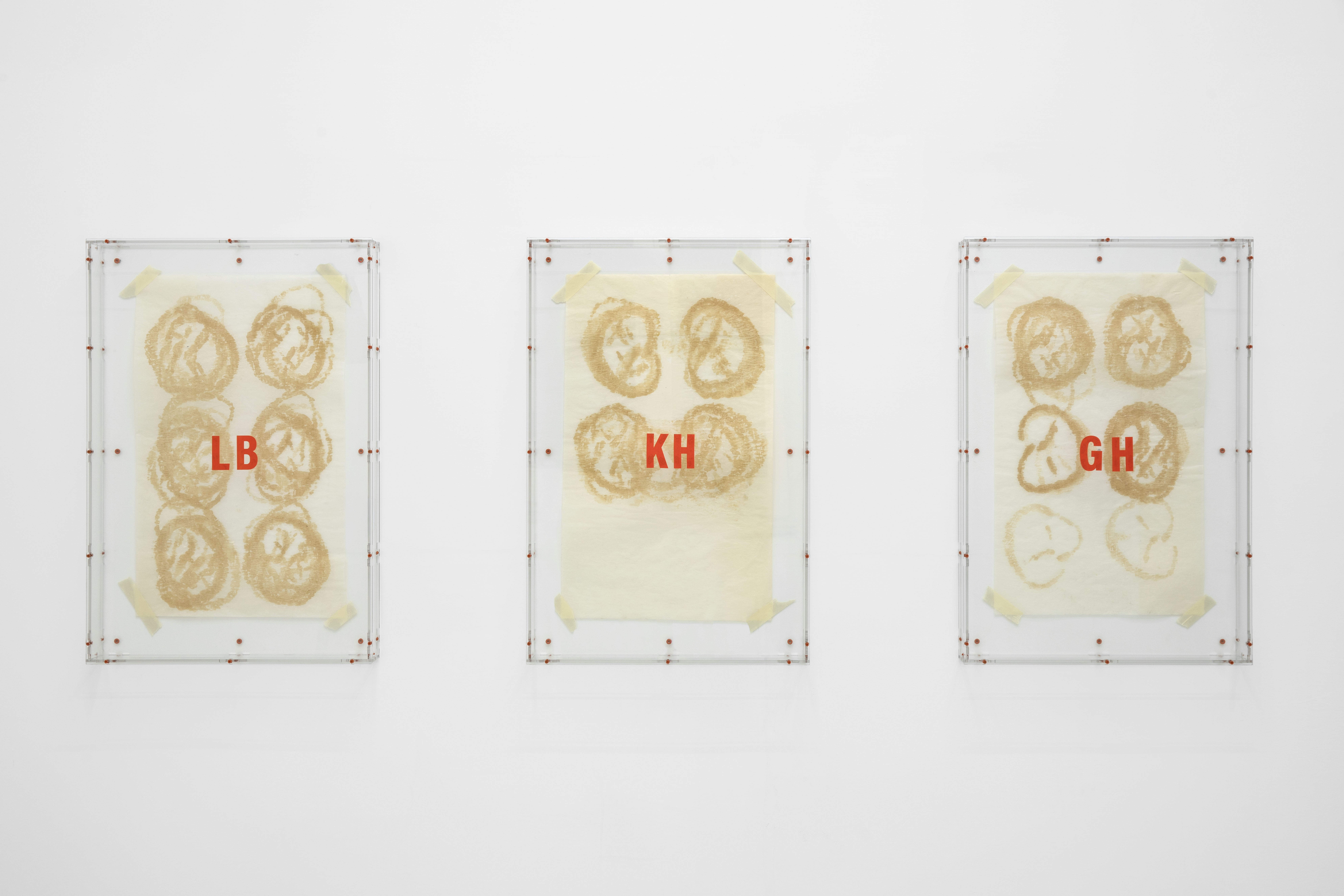

Prints, Dead Sea Scrolls, letters, the Turin shroud, a carbon copy of a missing text. These are some of the things that come to mind on viewing a set of neat, standard issue, Plexiglas boxes, each containing a large sheet of parchment paper covered in baked-on stains. The artist David Moser took the papers from a café called ‘Romeo und Romeo’ in Berlin, a place he once worked, and where every day frozen pretzels would be heated in an oven, swelling and sweating off the alkaline liquor in which they are coated, in soft, warm, looping, greasy patterns. The baking sheets were reused day-on-day, meaning that the residual marks from each batch would build up on top of one another, the trace of one set of doughy knots meeting and misregistering on another, collapsing the commonplace materiality of arte povera and the poppy seriality of a Warhol print. Crumbs as diamond dust, pretzel coating oxidizing like piss, the papers create a record of the mornings, an accrual of the everyday in this establishment. There, waves of customers would begin with night-workers and sex-workers finishing their shifts, and then continue later in the morning with customers who are beginning their day.

I like to think of these baking papers as writing, writing that is a kind of waste, a receipt of hunger, of chat, of exchange, that is both in concert and in tension with act of purchasing a coffee or a pretzel in the morning. Each transparent box also bears two or three orange vinyl letters, a monogram reminiscent of initials – AB, ET, LM – like a dedication, summoning the possibility that these are portraits, or missives, or memories specific to an individual. Where I start to imagine these as containers for a person, I start to think that they capture a kind of ectoplasm, a material of the spirit that leaks out, that cannot easily be read or defined by our systems such as language, such as a name. What, after all, is in a name, O Romeo, Romeo? Or should we say, David, David?

What’s David? It is nor hand nor foot / Nor arm nor face nor any other part / Belonging to a man. Yet the name is called out by many different voices from a device in the exhibition space, which also shows a film of shifting digital color options. They are all orange. Easy orange, GrindR orange, Substack orange, the orange of no-frills, of delivery drivers, the orange of speed, the orange of frictionlessness choice, of swiping, of taxonomy. Of Libras and statistics, of heights and body types – not hand nor foot nor arm – but ENFPs or INTJs, or securely attached or, blonde or brunette, of Barcelona to Heathrow, of groceries on demand. Still, what structures this film is not its totality, there is something that seeps from it that is more than the sum of its brand identities. It is a warm glow, like a fire, a light, that touches that which it falls on.

Laura McLean-Ferris

Rotoli del Mar Morto, lettere, la Sindone di Torino, una copia carbone di un testo scomparso. Queste sono alcune delle immagini che vengono in mente osservando una serie di ordinate scatole di plexiglas standard, ognuna contenente un grande foglio di carta da forno coperto da macchie cotte. L’artista David Moser ha raccolto questi fogli in un caffè di Berlino, Romeo und Romeo, dove aveva lavorato: ogni giorno, dei pretzel surgelati venivano cotti nel forno, gonfiandosi e sudando la soluzione alcalina con cui erano stati trattati, lasciando tracce morbide, calde, sinuose, unte. I fogli venivano riutilizzati giorno dopo giorno, e i segni di ogni infornata si sovrapponevano a quelli precedenti: i nodi di pasta lasciavano impronte che si incontravano e si disallineavano, facendo collassare la materialità ordinaria dell’arte povera con la serialità pop di una stampa di Warhol. Briciole come polvere di diamante, la glassa del pretzel che ossida come urina: questi fogli diventano un archivio delle mattine, un accumulo del quotidiano in quell’esercizio commerciale. I clienti arrivavano a ondate: prima i lavoratori notturni e le sex worker a fine turno, poi chi iniziava la giornata.

Mi piace pensare a questi fogli da forno come a una forma di scrittura. Una scrittura-rifiuto, una ricevuta della fame, del chiacchierare, dello scambio. Un gesto che si sovrappone ma anche entra in tensione con l’atto di acquistare un caffè o un pretzel al mattino. Ogni scatola trasparente reca inoltre due o tre lettere adesive in vinile arancione, una sorta di monogramma – AB, ET, LM – che ricorda delle iniziali, una dedica, evocando la possibilità che si tratti di ritratti, messaggi o memorie legate a individui specifici. Nel momento in cui inizio a immaginarle come contenitori di una persona, penso che trattengano una sorta di ectoplasma: una materia dello spirito che filtra fuori, che non può essere facilmente letta o definita da sistemi come il linguaggio, o come un nome. Che cos’è, in fondo, un nome? O Romeo, Romeo? O dovremmo dire David, David?

Cos’è David? Non è mano né piede / Né braccio né volto né altra parte / Appartenente a un uomo. Eppure, quel nome viene pronunciato da molte voci diverse, da un dispositivo presente nello spazio espositivo, dove è visibile anche un filmato che mostra in sequenza campioni di colore digitale. Sono tutti arancioni: arancione EasyJet, arancione Grindr, arancione Substack. L’arancione del low-cost, dei rider, della velocità. L’arancione della scelta senza attrito, dello swipe, della tassonomia. Dei Bilancia e delle statistiche, dell’altezza e dei tipi fisici – non mano, né piede, né braccio – ma ENFP o INTJ, sicuro o insicuro in attaccamento, biondo o bruno, da Barcellona a Heathrow, della spesa in consegna immediata. Eppure, ciò che struttura questo film non è la sua totalità. C’è qualcosa che filtra attraverso, qualcosa che supera la somma delle sue identità di marca. È un bagliore caldo, come un fuoco, una luce che tocca ciò su cui cade.

Laura McLean-Ferris

Photo credits Maurizio Esposito